Barnacles are crustaceans, the same group that contains the more familiar crabs and lobsters. This means, among other things, that they have an exoskeleton and jointed appendages. But they live attached to rocks, covered with a calcareous test, with no sign of those appendages (at least when the tide is out!).

|

| Adult barnacles. Photo from Wikipedia. |

When covered with water, though, their jointed legs (cirri) extend from those tests and catch phytoplankton that floats by.

|

| Feeding barnacles. The feathery things are the cirri. Still from Wikipedia. |

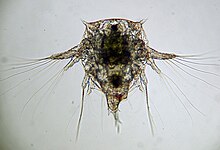

Because the adults live cemented to rocks, it is the larvae that do most of the dispersing. Barnacle larvae go through many molts in the plankton as a nauplius.

|

| Nauplius larva. Still Wikipedia. |

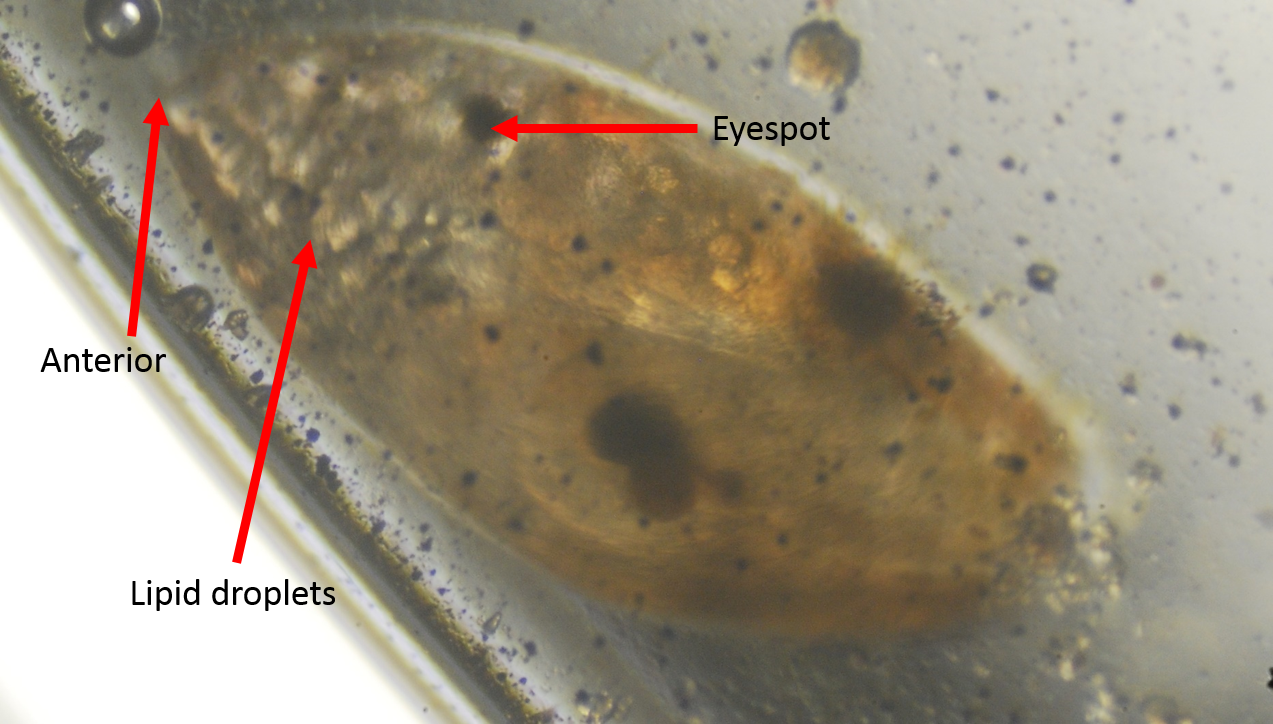

Then, when they are ready to settle and metamorphose, they turn into cyprids. It is these cyprids that search out a place to live, contacting various substrates and searching for the right physical and chemical conditions before metamorphosing into their adult form. Barnacle settlement is ubiquitous in these parts, and relatively easy to settle, so it has been a mainstay of larval ecology for decades. We arguably know more about how and why barnacles choose their settlement sites than any other taxa. It depends on a variety of physical factors (for example, they preferentially settle in cracks on rocks) and chemical factors (they are attracted to proteins produced by conspecifics).

Here is one of the cyprids I collected this weekend.

|

| A cyprid larva. Many lipid droplets at the anterior end provide buoyancy and energy for the larva. |

I have thousands in the lab right now -- if I give them the appropriate settlement cues, I'll be able to watch them metamorphose, and the barnacle life cycle will be complete. (Well, except for gamete production and mating...perhaps left for a future post?)

No comments:

Post a Comment